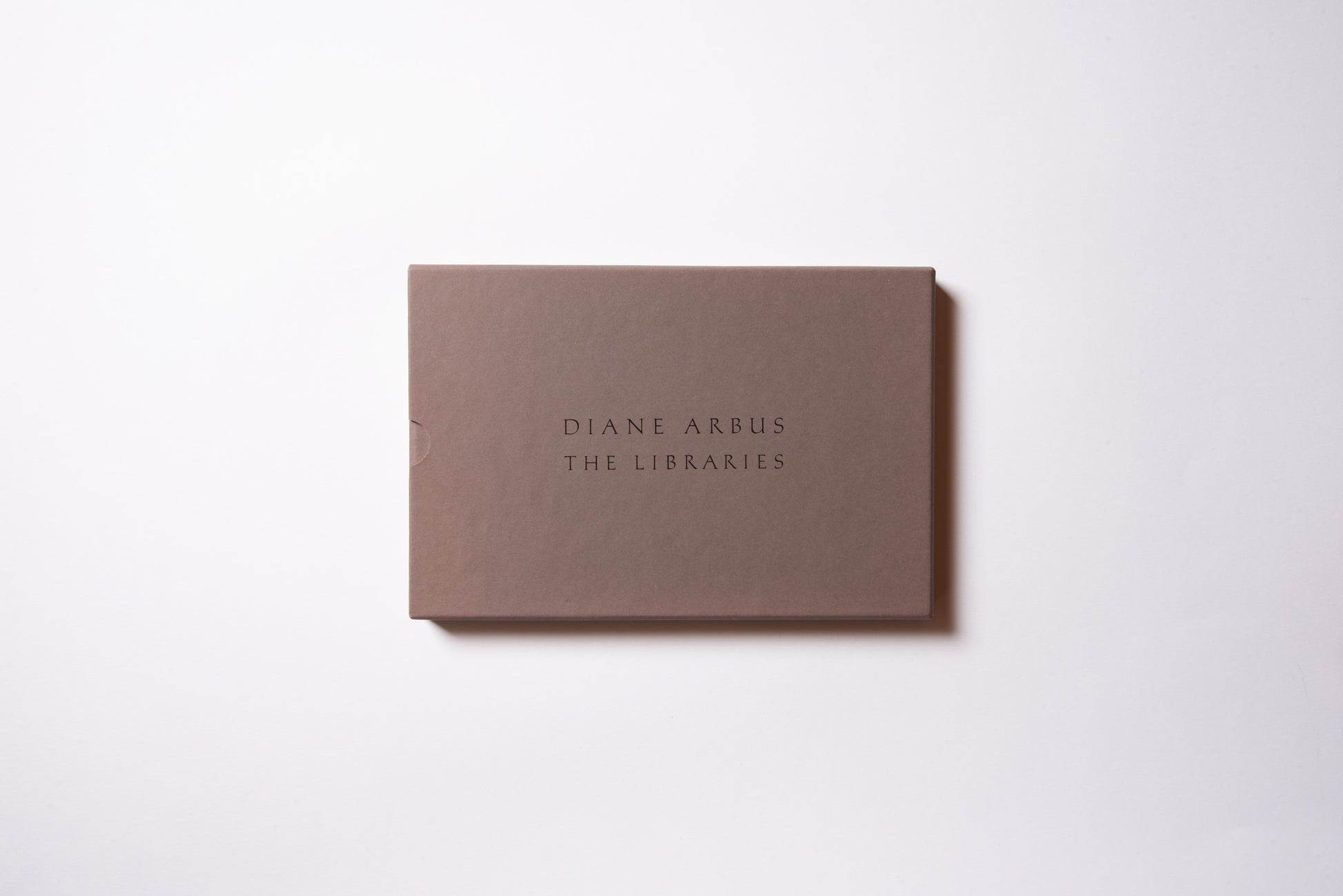

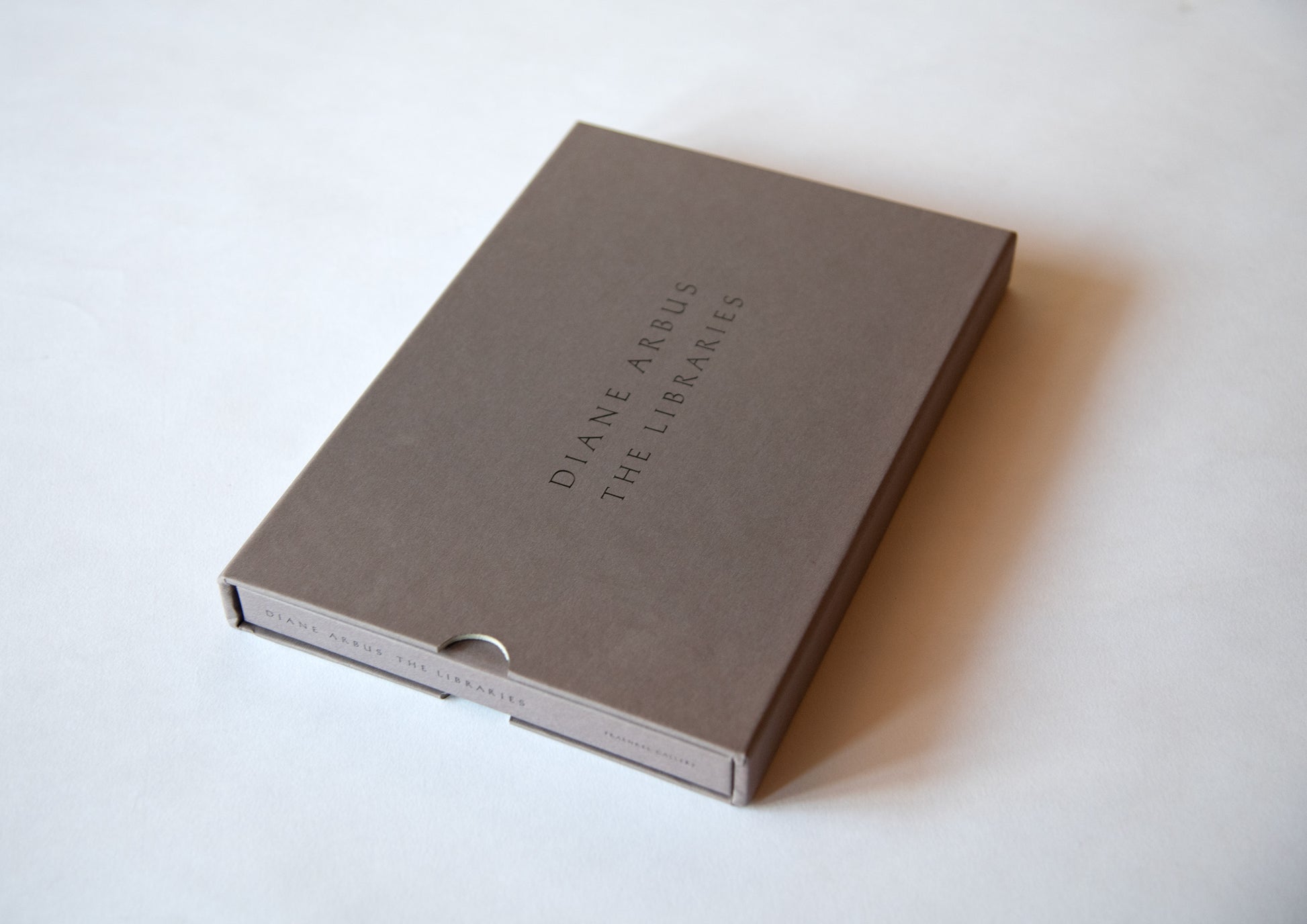

The Libraries: Diane Arbus

Bibliographic Details

- Title

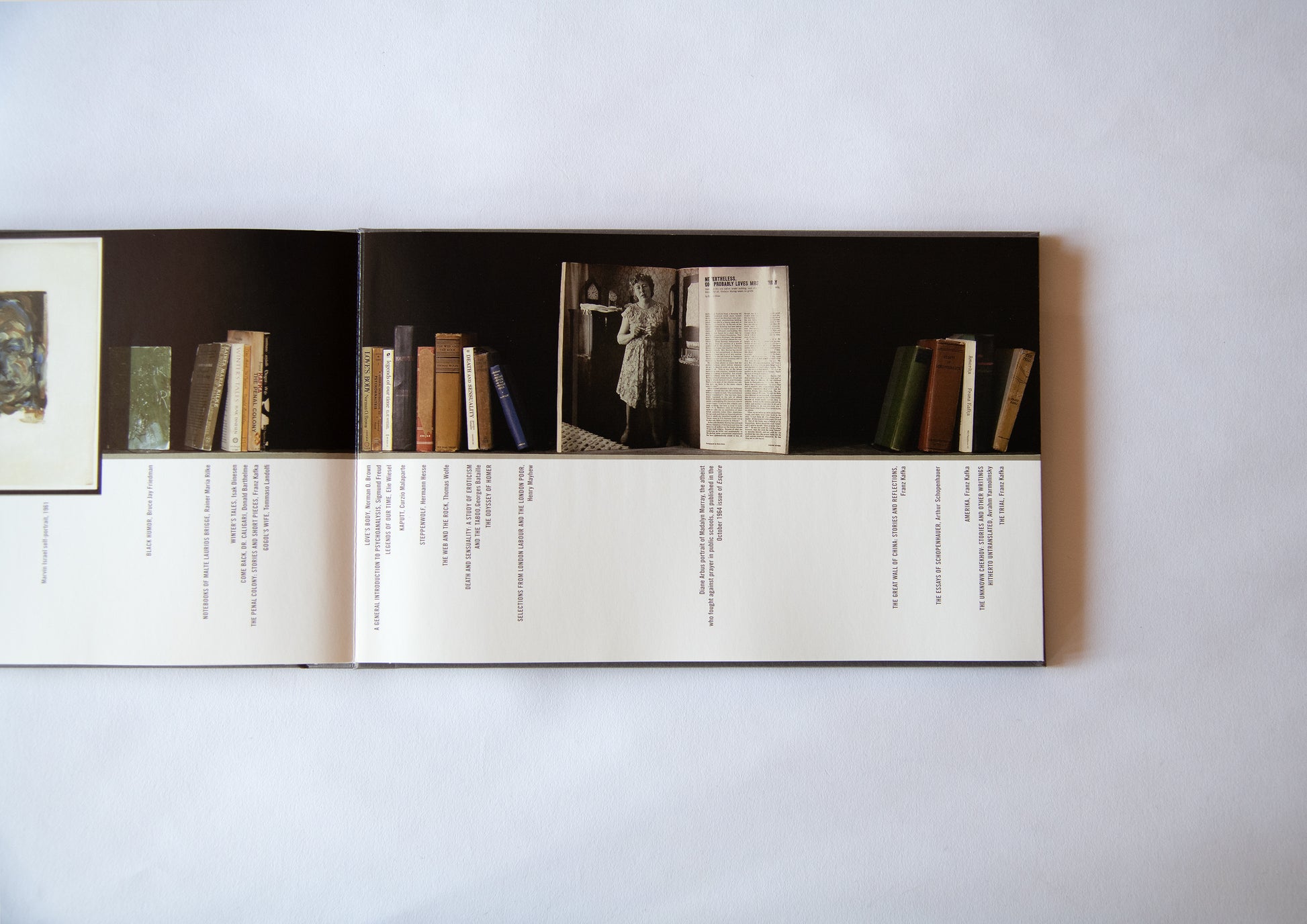

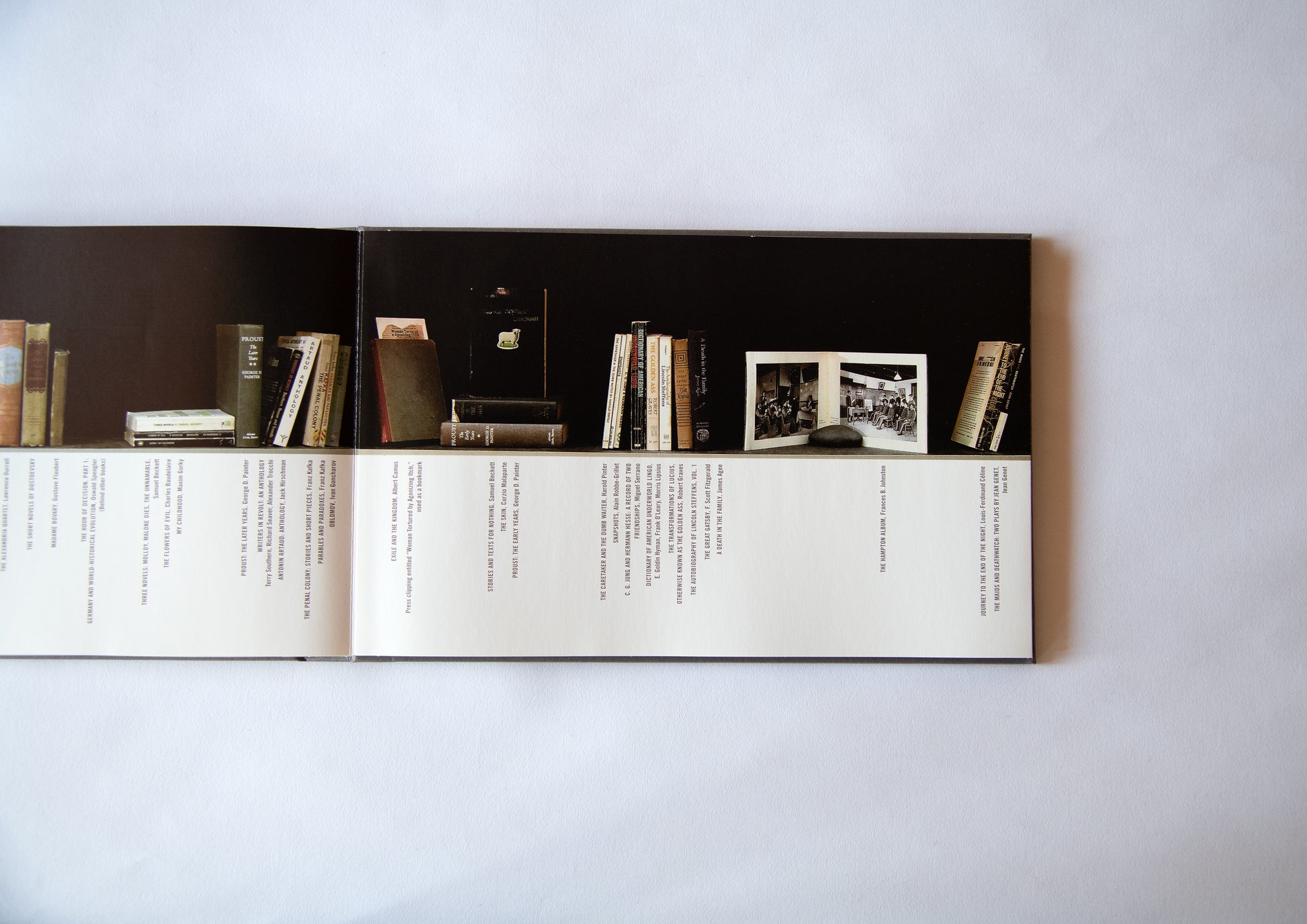

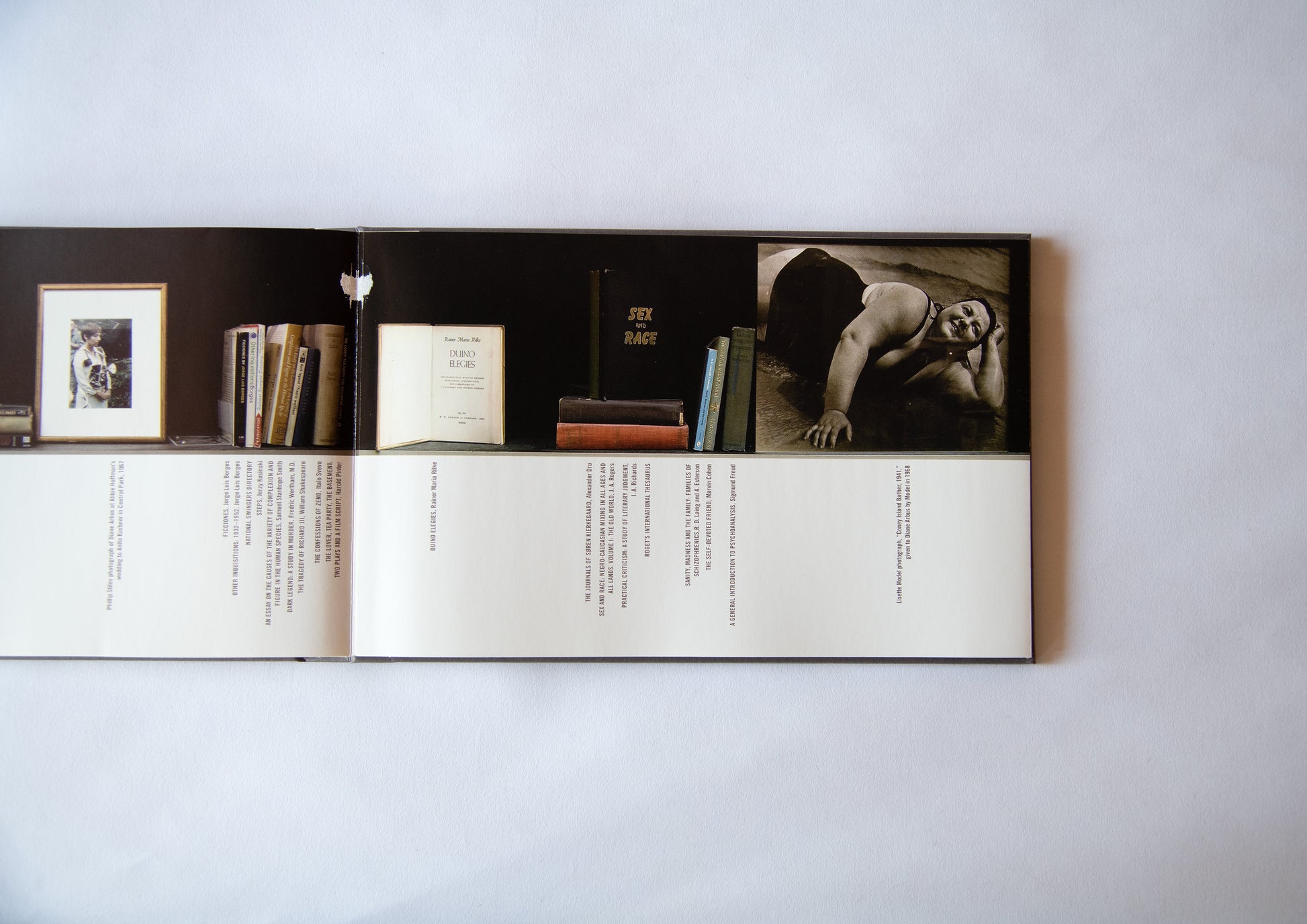

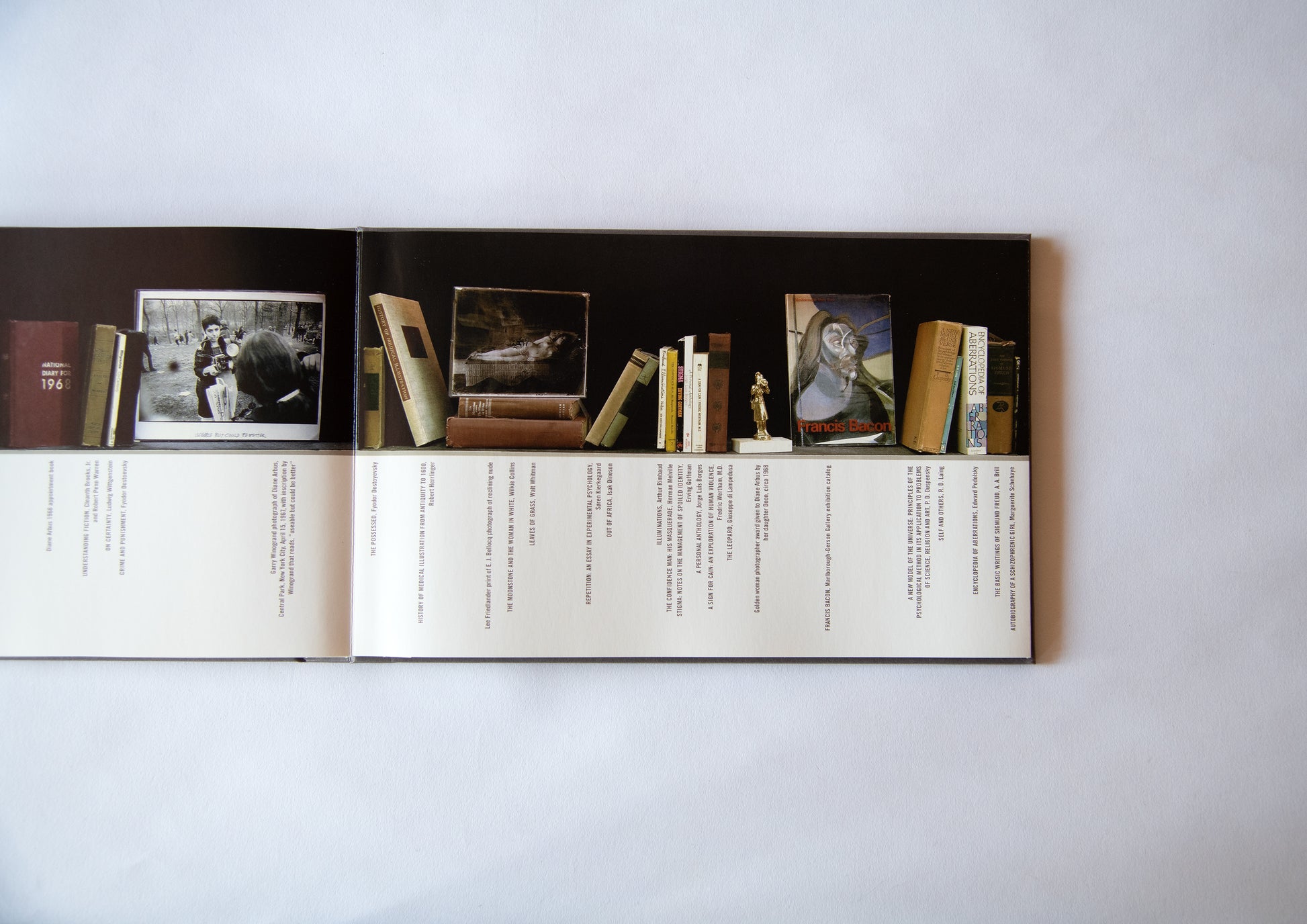

- The Libraries

- Author

- Arbus, Doone And Diane

- Artist

- Diane Arbus / ダイアン・アーバス

- Editor

- Mary Bahr

- Designer

- Yolanda Cuomo, Kristi Norgaard

- Images

- Photo by Megan Lewis

- Publisher

- Fraenkel Gallery

- Year

- 2004

- Size

- h195 x w290 x d26 mm

- Weight

- 790g

- Pages

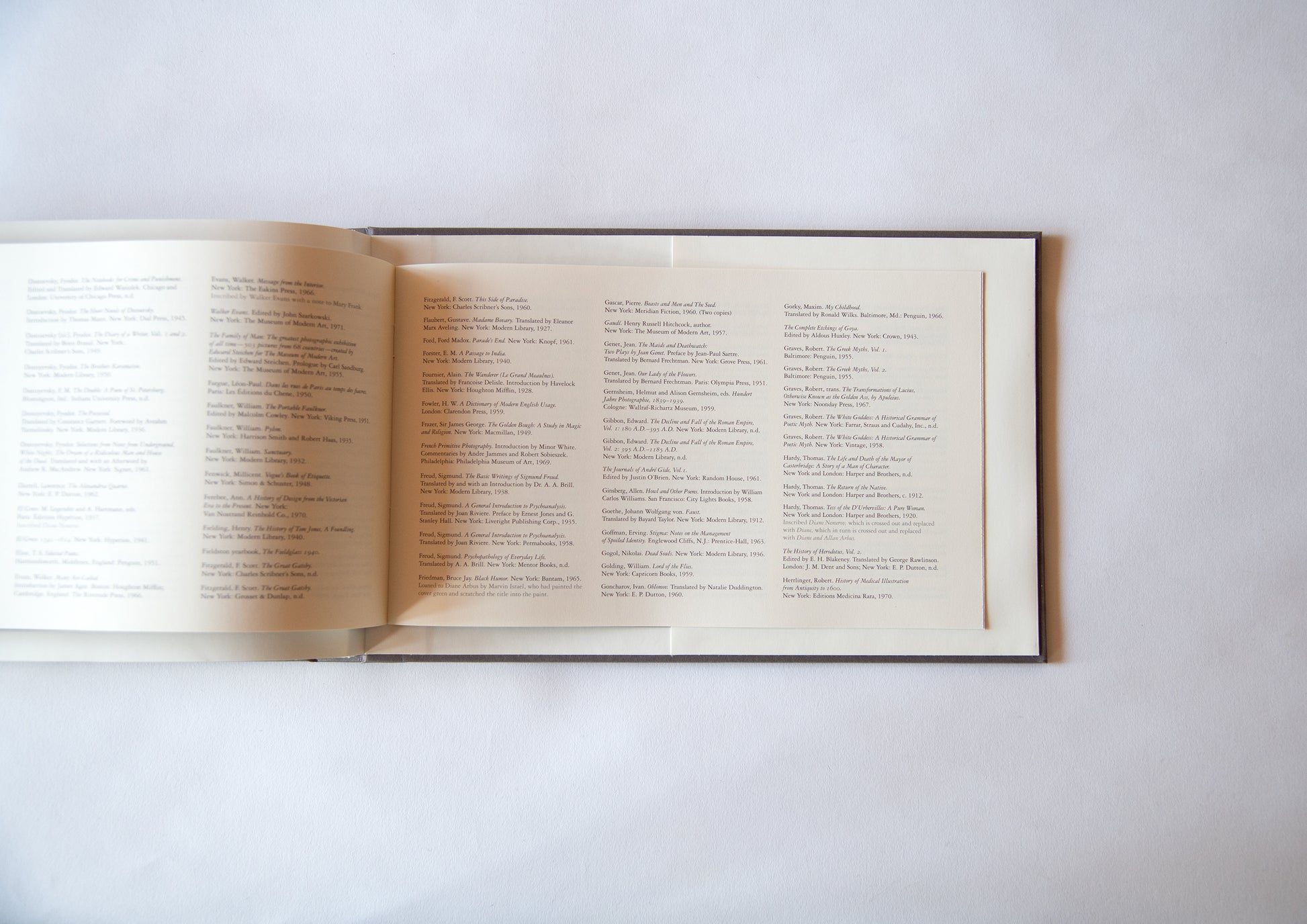

- 32 pages + 12 pages Bibliography

- Language

- English / 英語

- Binding

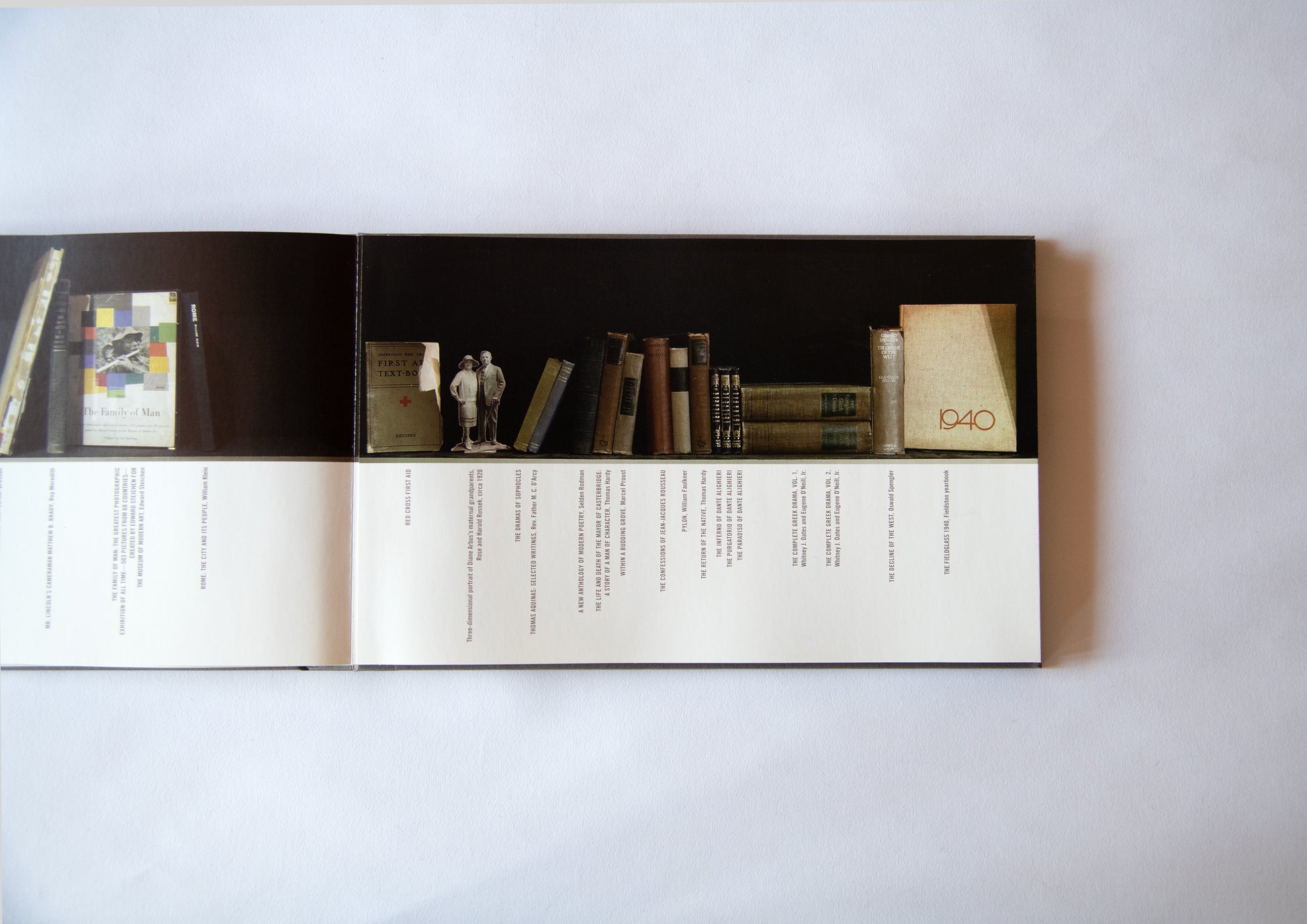

- Accordion-fold (leporello) binding/ 蛇腹本・函入

- Condition

- New / 新品

The remaining books

The mysterious photographer

He will tell you in secret.

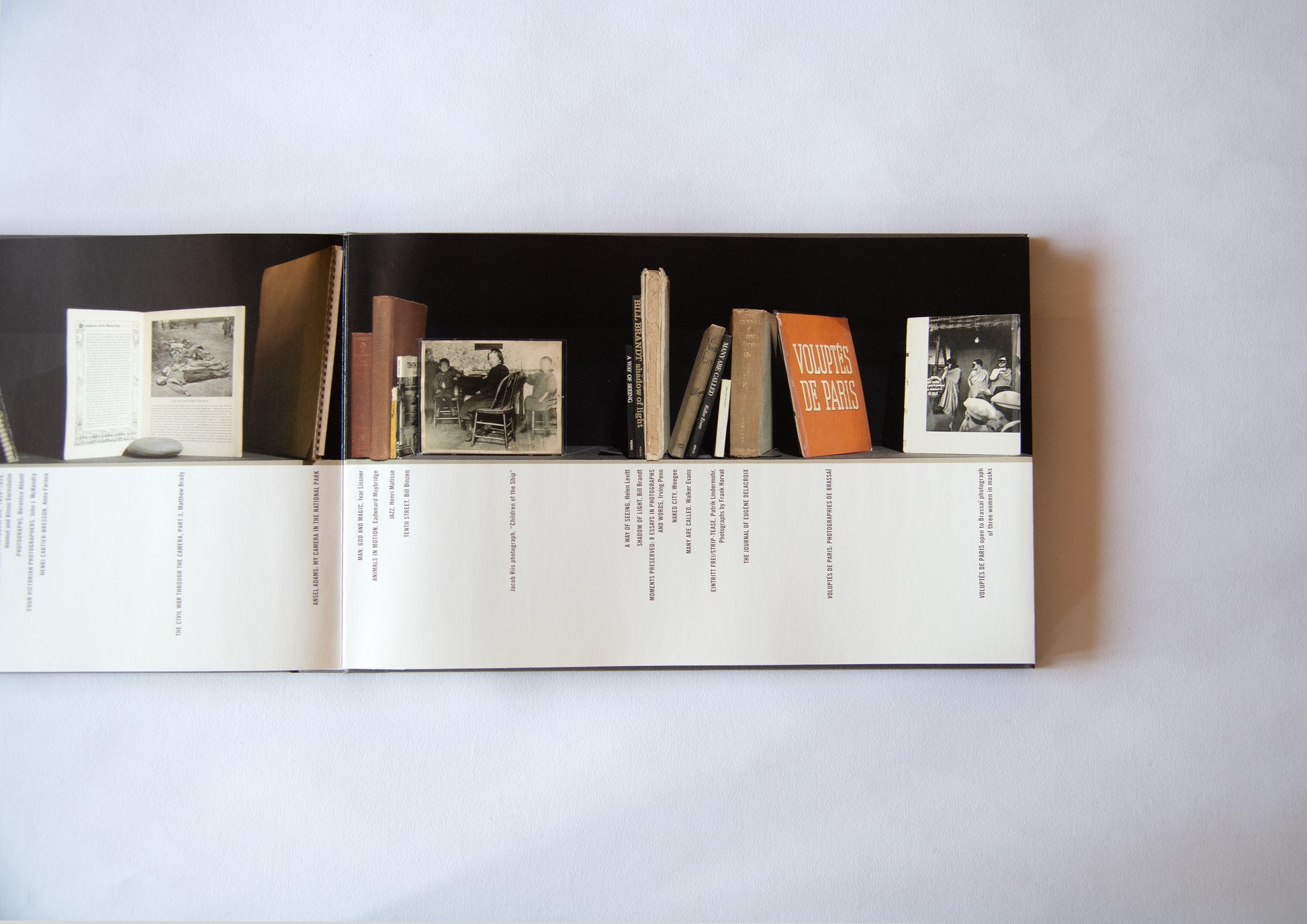

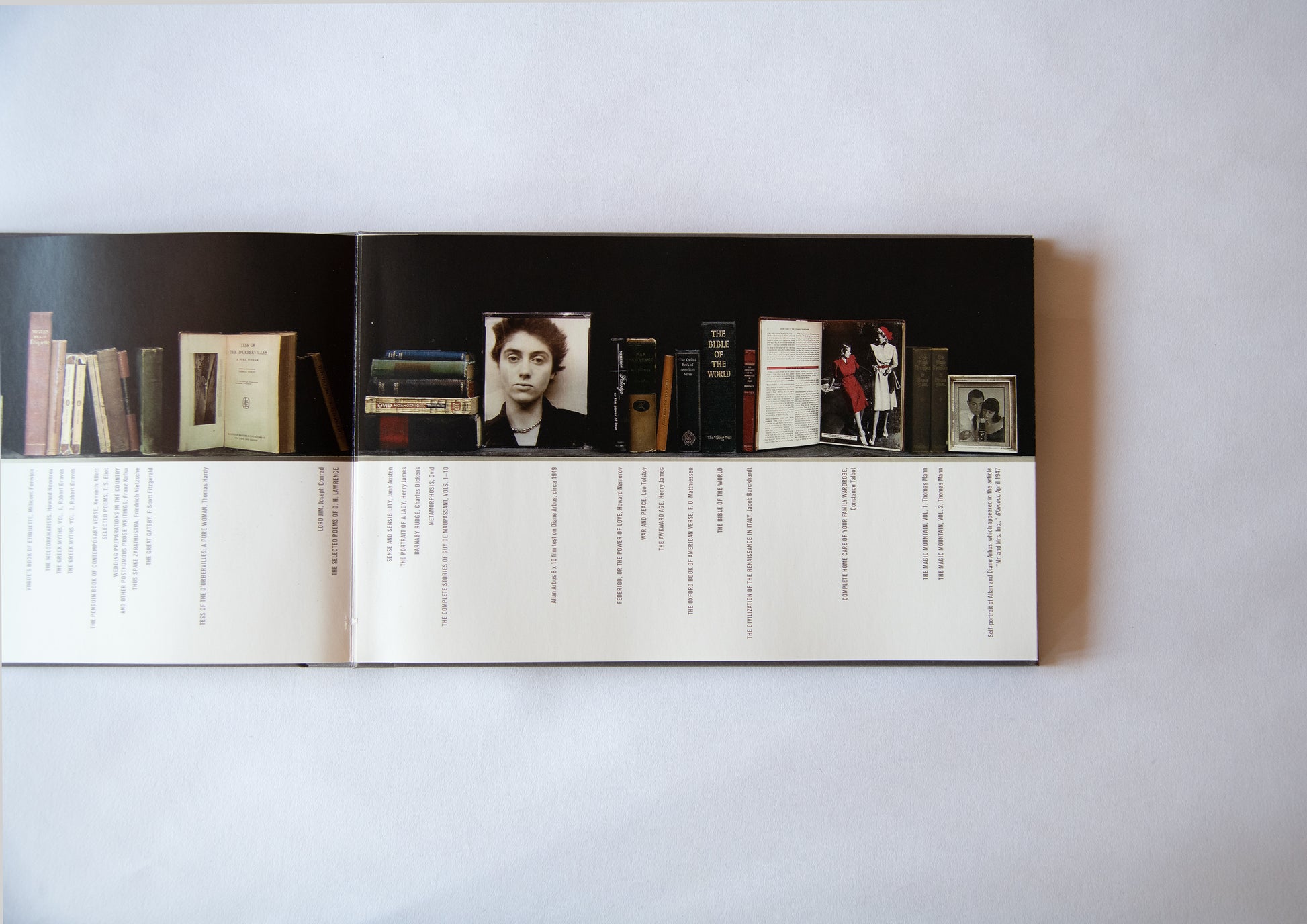

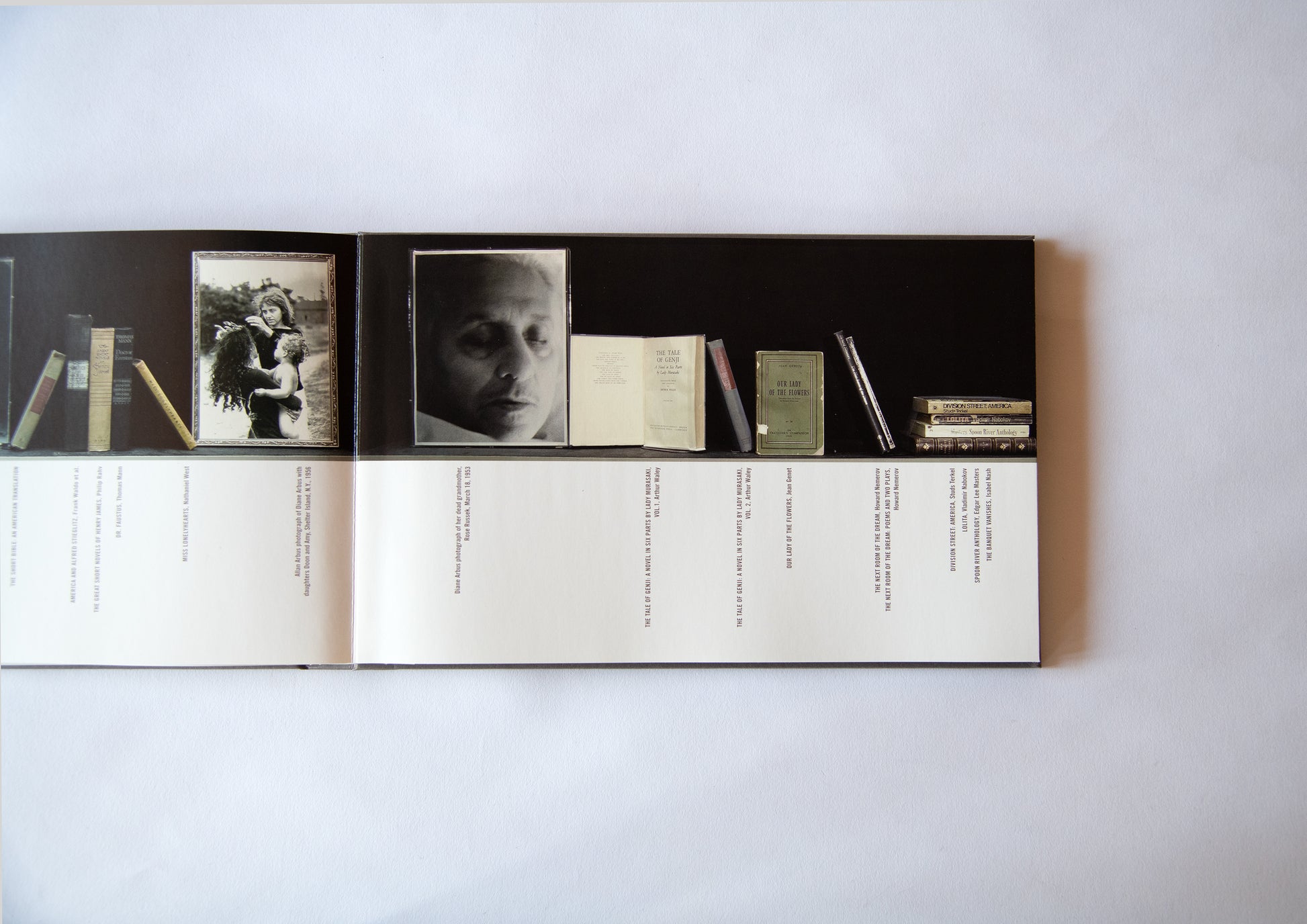

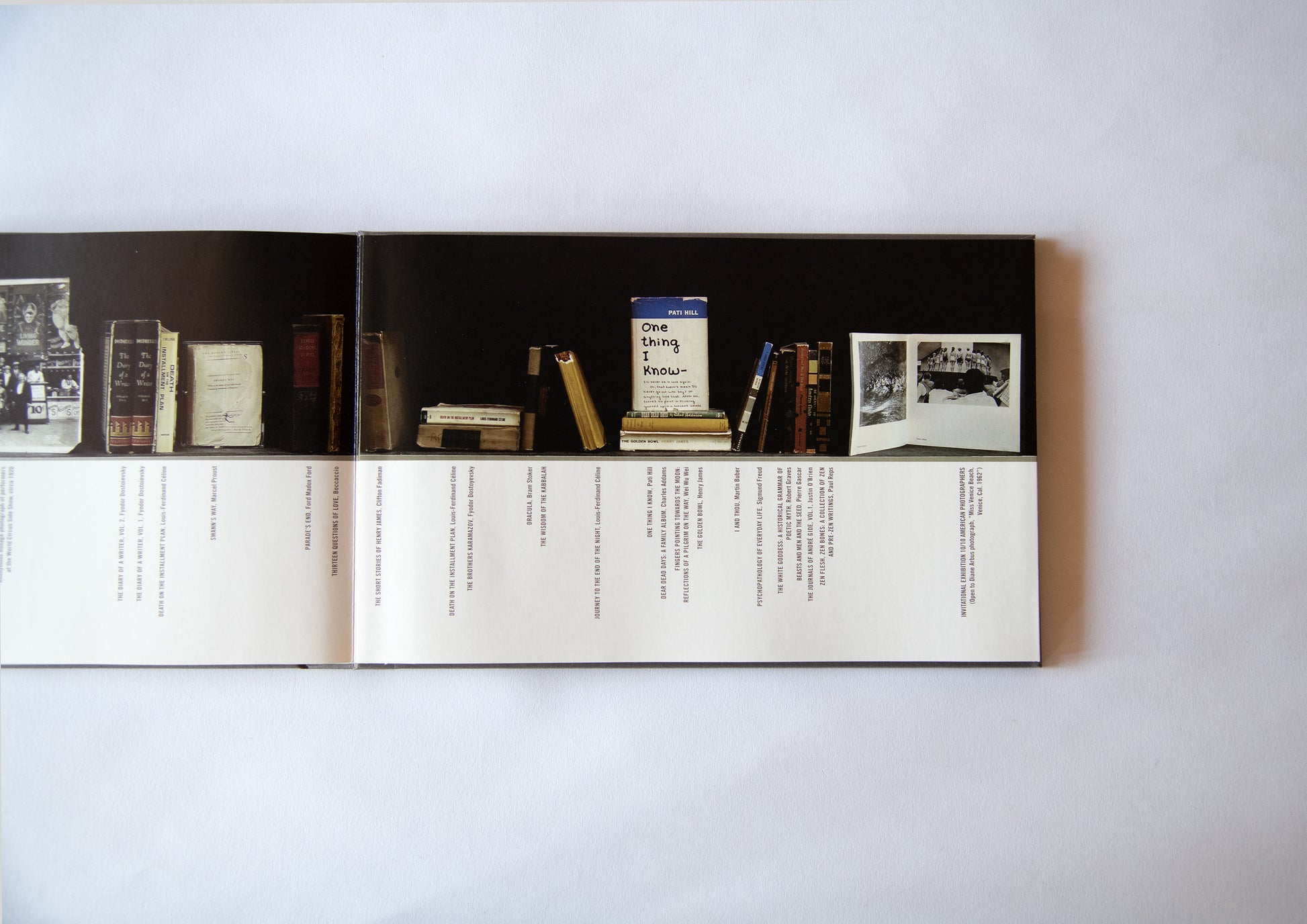

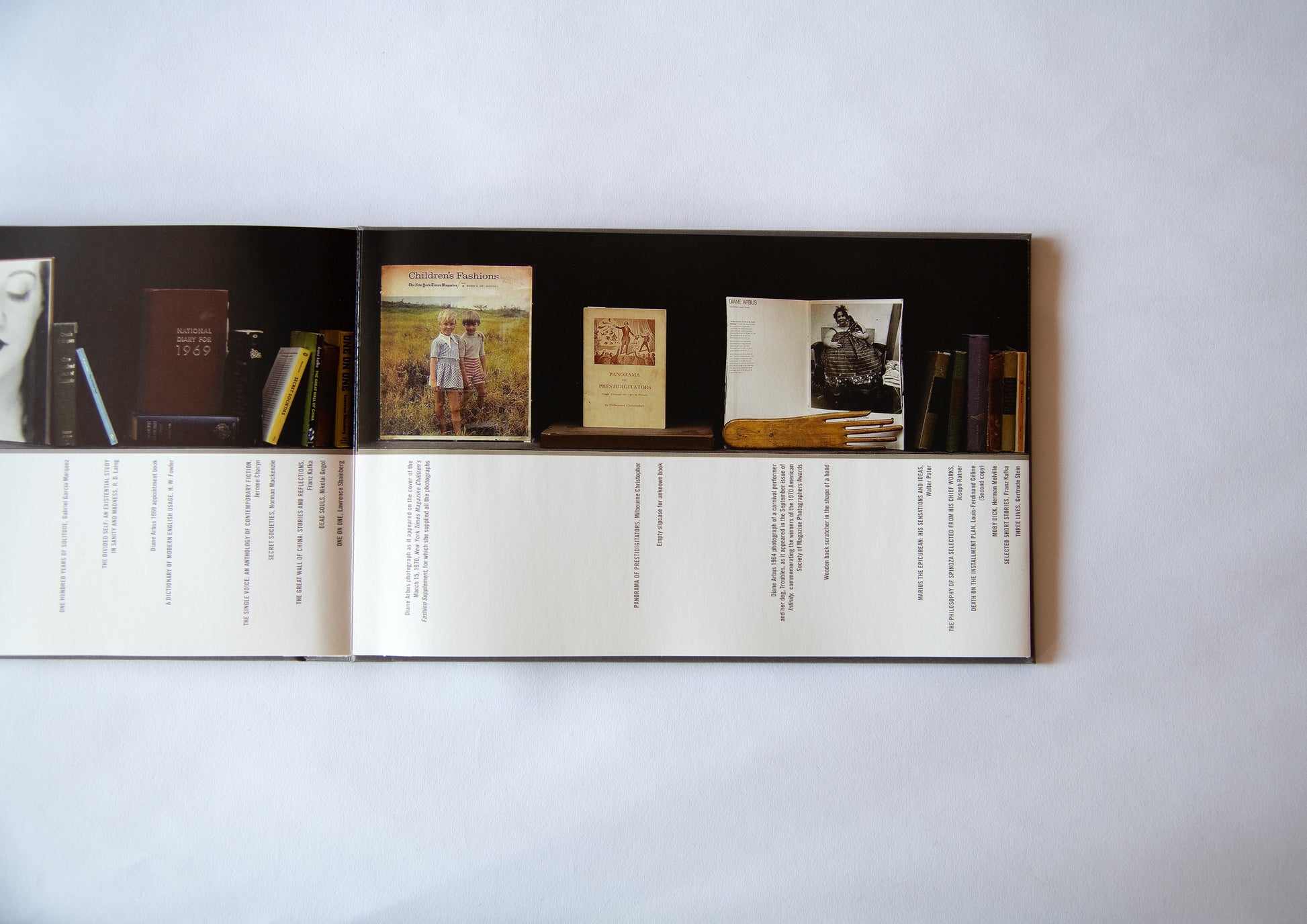

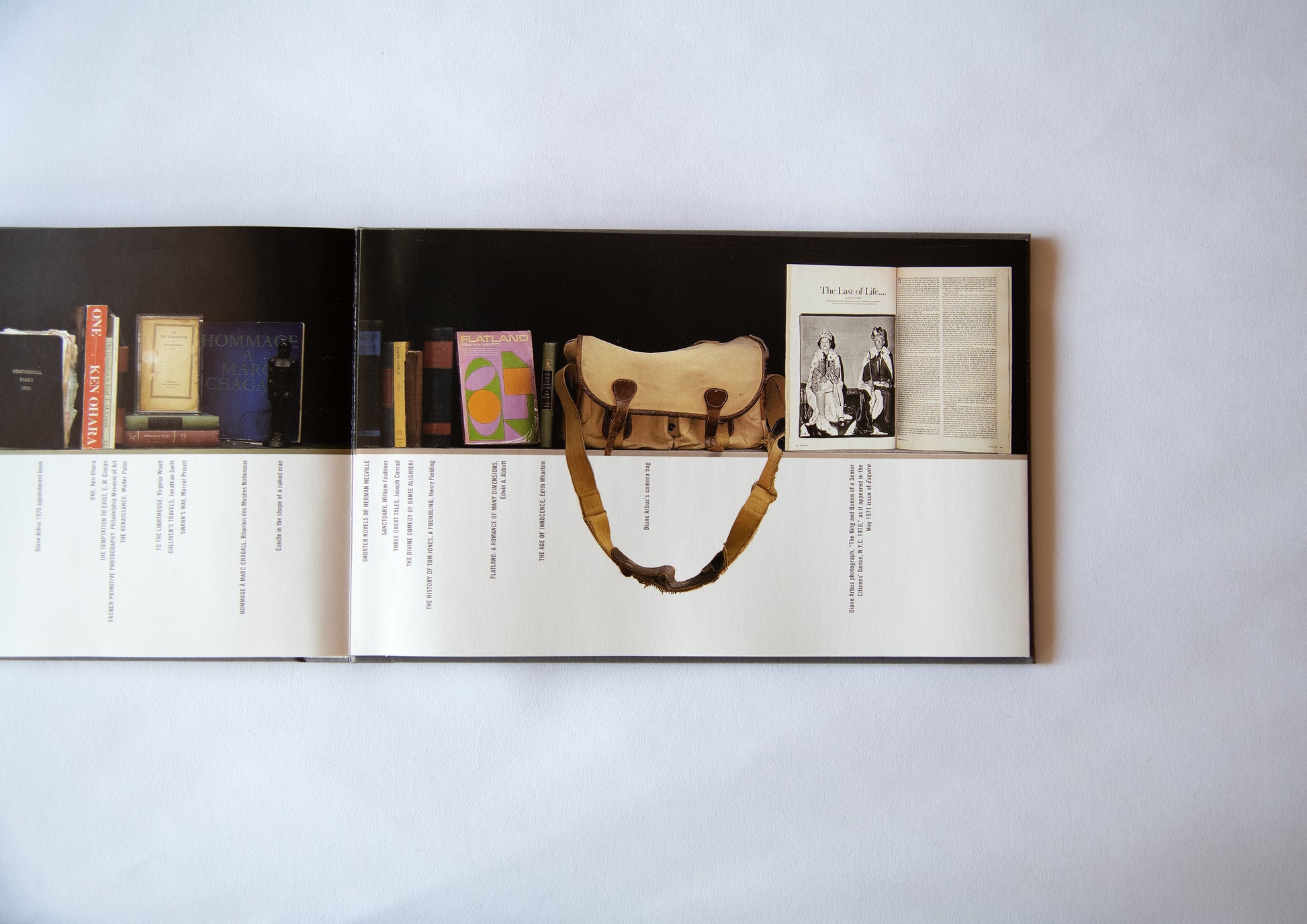

This book documents the private book collection of photographer Diane Arbus (1923-1971). The book is accordion-folded, and when opened, reveals a horizon of over eight meters of bookshelves. It is a book that will never cease to intrigue you as to what books she once read and held on to, after continuing to photograph those who were marginalized from society with a straightforward eye and meeting her sudden and mysterious end.

Susan Sontag once said that her bookshelf was "in my head...a map of my brain." I know exactly how she feels. A personal collection is an extension of one's mind, and a bookshelf that maps out the interior of the head is a map where the owner's interests intersect. For some people, having their private bookshelf seen is more embarrassing than having someone see them naked. As part of my job, I select books, display them, design bookshelves, and plan publications, and I have had the good fortune of getting a peek into many private collections.

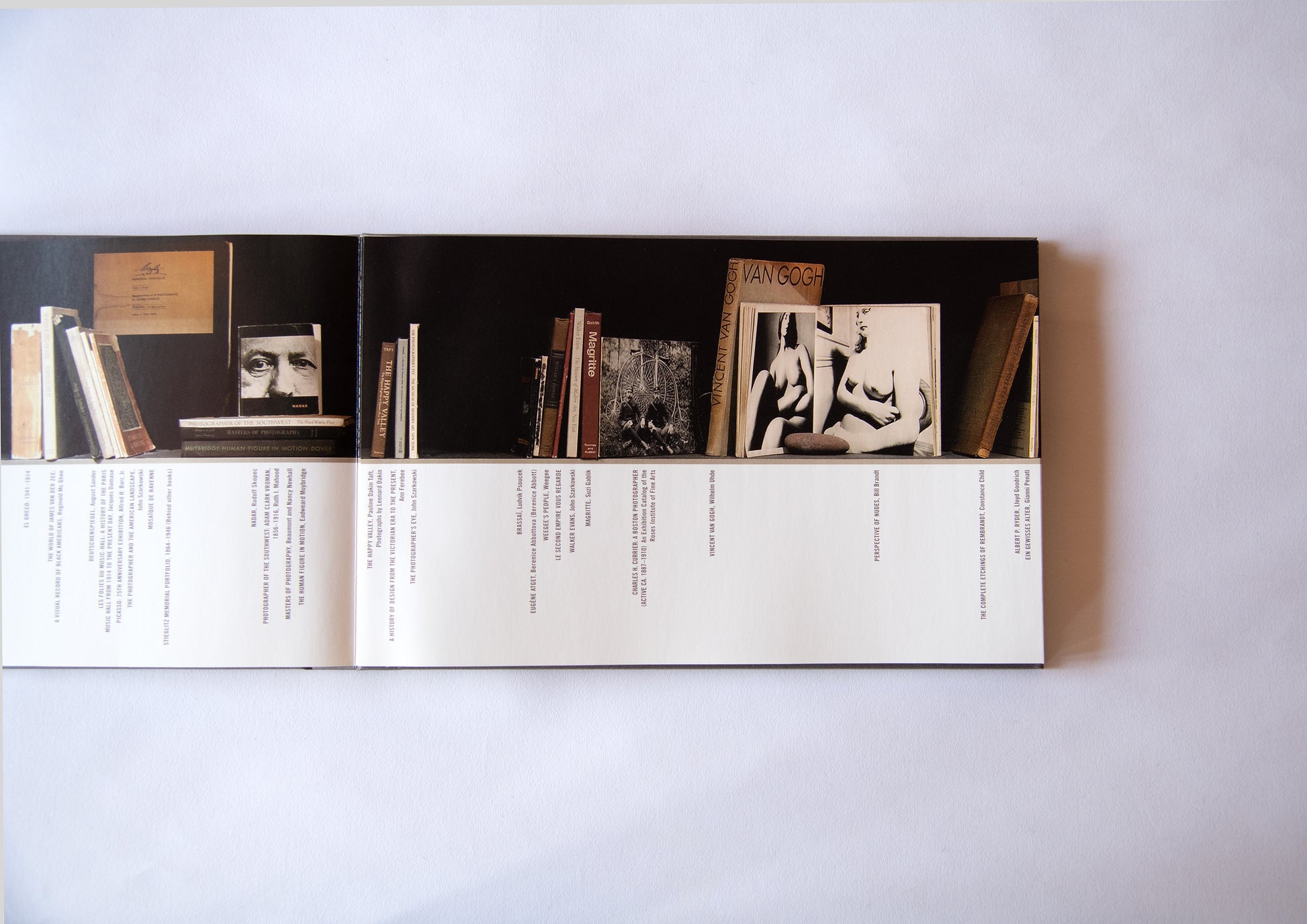

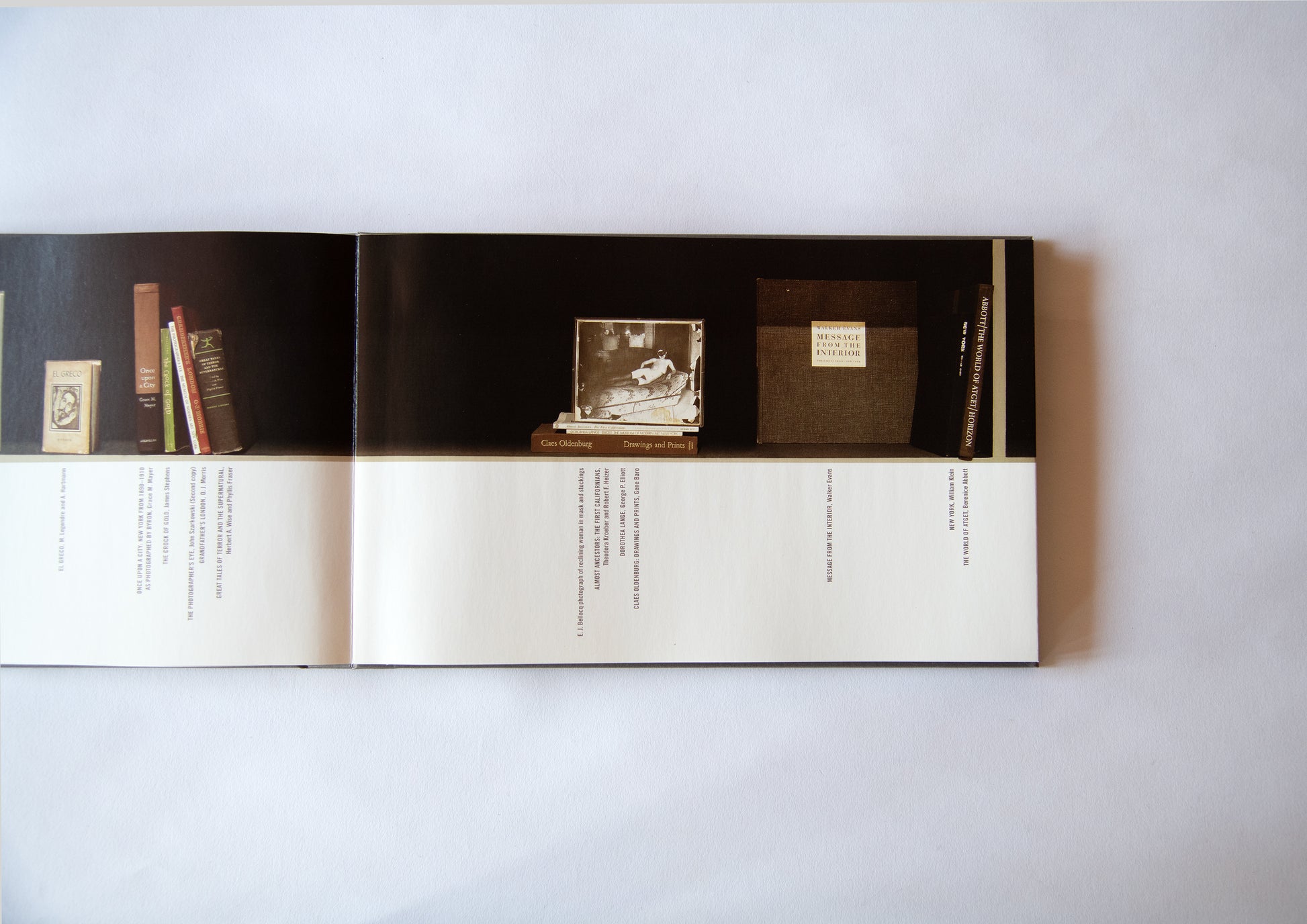

Diane is a photographer, so there are many photo books on her bookshelf. There are many masterpieces from the early days of photography, such as Nadar, Atget, Lartigue, Bresson, Irving Penn, and Stieglitz. There are also magazines that feature projects and interviews that Diane herself was involved in, such as Edward Steichen's "The Family of Man." Even so, there seem to be few books that have been donated. The collection is carefully selected, and each is loosely divided into several small groups. This is probably proof that Diane has had a deep relationship with books, treating them as an extension of her body. Among the books by her friend Avedon, a portrait of the 34th President of the United States, Eisenhower, which Avedon gave to Diane, is sticking out from the shelf. If you look closely, you can see self-portraits of Diane taken by her husband Alan and another photographer peeking out from between the books. EJ Bellocq's portraits of mysterious prostitutes and anonymous photographs of circus troupes that appear out of nowhere may have been images that Diane used as reference for her photographs.

He also seems to have read a lot of novels, literary books, and humanities books. Many of the paperbacks have cracked spines, probably because they were read so many times. Just by looking around, you can see the original (or English versions) of Dante's Divine Comedy, Homer's The Odyssey, Aeschylus' Greek Tragedy, Henry James' The Wings of the Dove, Proust's In Search of Lost Time/Swann's Way, Georges Bataille's Eroticism, Dostoevsky's The Brothers Karamazov, Kafka's The Trial, Borges' Fantastic Books, Rilke's Duino Elegies, Celine's Journey to the End of the Night, James Fraser's The Golden Bough, Wittgenstein's The Problem of Certainty, Virginia Woolf's To the Lighthouse, Garcia Marquez's One Hundred Years of Solitude, Emil Cioran's The Seduction of Existence, and Abbott's Flatland. In Albert Camus's "The Exile and the Kingdom," an article titled "Woman tortured by agonizing itch" is inserted as a substitute for a bookmark. Such substitutes and repurposed objects, and the sight of seemingly unrelated candles, trophies, and rocks lined up alongside books, are the chaotic charm of a personal library.

Curious about the layout of the books, I looked over the room from a bird's-eye view and noticed that next to art books by Bruegel, Da Vinci, and Goya was Bresson's The Decisive Moment, with a Matisse cutout on the cover, and next to that was a magazine with a portrait cut-out of August Sander, a German portrait photographer to whom Diane had been compared and referenced even during her lifetime.

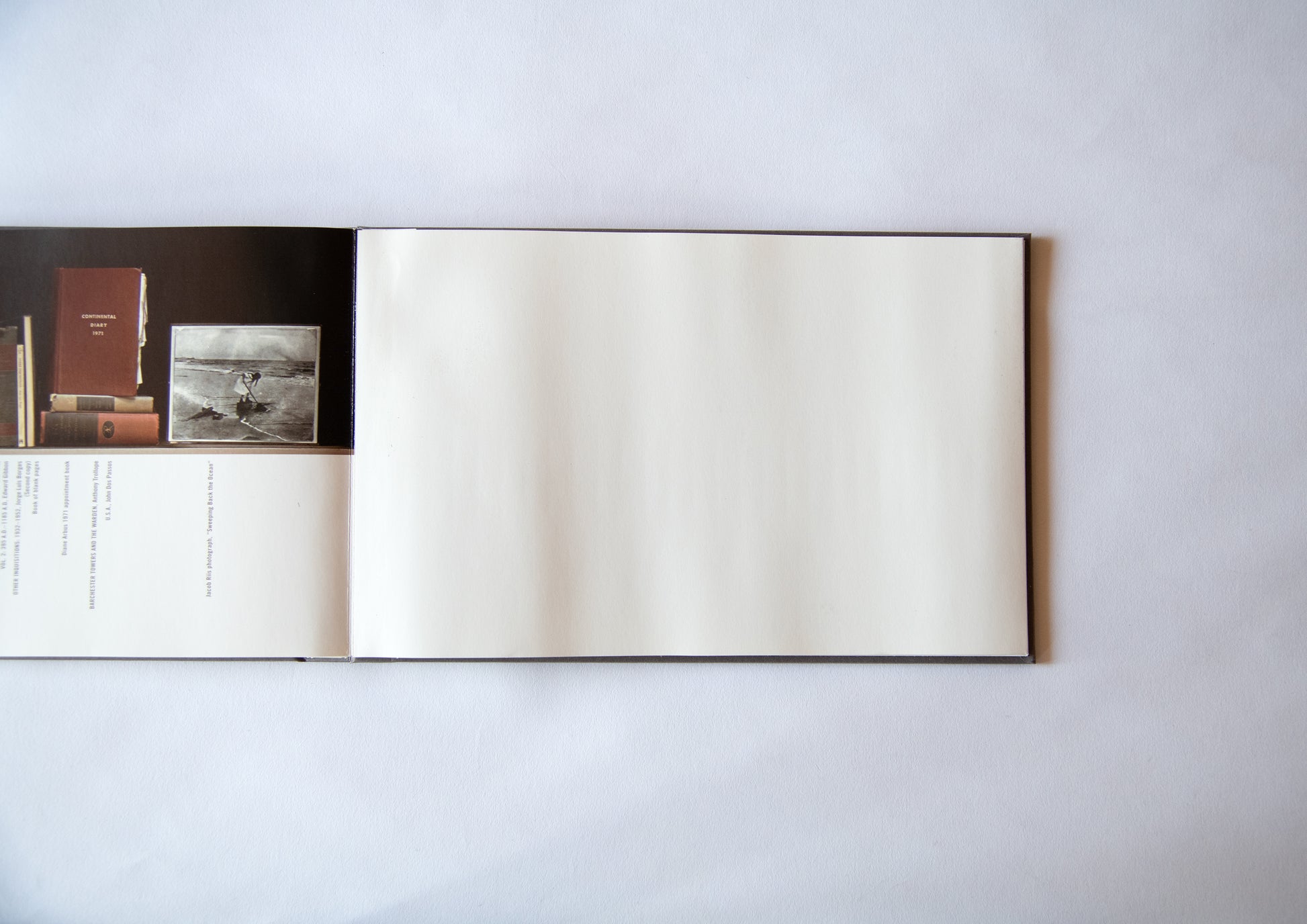

In another corner, next to a portrait of her grandmother that she had photographed, are volumes 1 and 2 of The Tales of Genji, next to Jean Genet's Our Lady of the Flowers, and next to that is The Next Room of the Dream, a collection of poems by her brother, the poet Howard Nemeroff. And on the last page of the book, there is a diary from 1971, the year Diane died, placed like a gravestone.

Hmm, it's a book that becomes more enjoyable every time I look at it.

I would like to take a moment to look back on the life of Diane Arbus, whose works are featured on this bookshelf.

Born in 1923 to a Jewish family in New York, Diane grew up in Central Park West, where her wealthy family always had a maid, a cook, a chauffeur and a nanny. Her father, David Nemeroff, ran a fur and women's clothing store called Russek's Department Store on Fifth Avenue in New York. At the age of 13, she met advertising photographer Allen Arbus, who frequented her father's store, and they married after Diane turned 18. She gave birth to two daughters (Doon in 1945 and Amy in 1954), and while raising her children, she began helping her husband Allan with photography for fashion magazines such as Harper's BAZAAR as an assistant photographer. The film Fur: An Imaginary Portrait of Diane Arbus (2006) depicts the inner conflict she was going through at this time and her awakening as a photographer.

She discovered photography through her husband Alan, and after divorcing him in 1959, she studied under Berenice Abbott, Alexey Brodovitch, and Lisette Model, while establishing her own style as a photographer. In 1960, her first photo essay was published in Esquire magazine, and in 1963 and 1966, she was awarded Guggenheim Fellowships, and began a series of photographs titled "American Rites, Manners, and Customs." In 1967, she was selected as one of three people (the other two being Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand) to show the potential of documentary photography in the groundbreaking exhibition "New Documents," organized by John Szarkowski, the director of photography at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York. This marked a decisive turning point for her.

Diane was a photographer who captured her subjects head-on. She focused on the square format, and with a twin-lens reflex camera such as a Rolleiflex or Mamiya C33 hanging from her neck and a flash on her shoulder, she went out to photograph "freaks" who lived ordinary lives just like everyone else. Her style was to visit the places where they lived, rather than inviting them to a photography studio. Diane called these people "aristocrats of the spirit," even though they were looked upon strangely as dwarves, giants, hermaphrodites, mentally ill people, and freak show performers. She stood in front of her subject, positioned herself facing them as if they were a mirror, and fired the flash directly in front of them.

Her photographs have been praised and criticized. In particular, she has been criticized for "taking pictures of unfortunate people and exploiting them." In her mid-40s, she was devastated by depression and hepatitis, which she suffered from in 1966. And her artistic, intellectual and unstable days came to an all-too-early end. On July 26, 1971, four years after the "New Documents" exhibition, Diane wrote the words "The Last Supper" in her diary, lay in her bathtub fully clothed, and cut her wrists. Although she is now remembered as a legendary photographer, her career was short, lasting less than 10 years. Although she never published a single photo book during her lifetime, her posthumous publication "Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph" is still in print around the world.

Supplementary

She was the first photographer to have her work selected for the Venice Biennale, a feat she achieved the year after her death. From 1972 to 1975, a major retrospective of her work was held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, which traveled to the United States and Canada. In 2003, a major retrospective of her work, "Diane Arbus Revelations," was held at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, which toured museums in the United States and Europe until 2006.A major European retrospective began at the Jeu de Paume in Paris in October 2011, and traveled to Winterthur (Switzerland), Berlin (Germany), and Amsterdam (Netherlands) until 2013. In 2016, the Met Breuer held a smash hit exhibition titled "In the Beginning," focusing on unpublished photographs from the first seven years of her career (1956-1962). The exhibition traveled to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Malba in Buenos Aires, and the Hayward Gallery in London. In 2018, the Smithsonian American Art Museum held an exhibition titled "Diane Arbus: A box of ten photographs." Diane Arbus's life as a pioneer in the acceptance of photography as a "serious" art form is still legendary.

This book was published as a record of the personal library exhibited in the retrospective "Diane Arbus Revelations," which was held at seven museums, including the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, from 2003 to 2006.

«Major Publications»

Diane Arbus (Aperture, 1972)

Magazine Work (1984)

Untitled (1995)

Diane Arbus Revelations (2003)

Diane Arbus: A Chronology (2011); Silent Dialogues

Diane Arbus & Howard Nemerov (2015)

In the Beginning (2016)

Diane Arbus: A box of ten photographs (2018)

Diane Arbus Documents (2022)

Text by Osamu Kushida